When I look back at my early days of reading John Dickson Carr’s work, it’s almost obscene. Hit after hit after hit after hit. This wasn’t exactly an accident – I had done my research on the author. At the same time, I wasn’t exactly being greedy. My goal was to mix up the consensus classics with some well regarded books that flew a bit below the radar. It just so happened that a lot of those below the radar books are astoundingly good.

When I look back at my early days of reading John Dickson Carr’s work, it’s almost obscene. Hit after hit after hit after hit. This wasn’t exactly an accident – I had done my research on the author. At the same time, I wasn’t exactly being greedy. My goal was to mix up the consensus classics with some well regarded books that flew a bit below the radar. It just so happened that a lot of those below the radar books are astoundingly good.

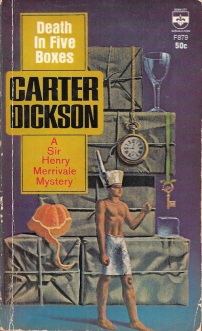

My early days were also constrained by the books that I owned at the time. One particular bulk purchase that I made towards the beginning was a package of early Merrivale titles in 1960’s Berkley Medallion editions. Not only did these prove to be solid selections, but they had some great cover art as well.

The Judas Window, The White Priory Murders, The Red Widow Murders, The Reader is Warned, She Died a Lady, The Ten Teacups, The Unicorn Murders… That’s an actual run of books that I went through, albeit with several classic Dr Fell and non-series books mixed in. It’s an absolute glut. Not only will the astute Carr reader recognize that these are pretty much the best of the best Sir Henry Merrivale books published under the guise of Carter Dickson, but they’ll also recognize that all but She Died a Lady fall under the true classic early run of the series (1934-1940). If there’s anything closer to an impossible crime bender, I’d like to know about it.

Well, that was a fun jaunt, but my Merrivale reading has dried up since then. Since that time, I’ve been chugging my way through the good (The Gilded Man, Seeing is Believing), the decent (My Late Wives, The Curse of the Bronze Lamp), and the flat out bad (Night at the Mocking Widow, The Cavalier’s Cup). My only shining stars in the past 18 months have been The Plague Court Murders (1934) and Nine — and Death Makes Ten (1940). This has emphasized in my mind that the Merrivale titles were best up until 1940, and then took a gradual decline until the end. The early H.M. works consistently provided some of Carr’s tightest impossible scenarios and nearly always delivered when it came to the solution. More importantly, they were tight engaging reads with little filler.

The point of this rambling review of the Carter Dickson library is that it’s been a long time since I really basked in the light of a classic-era Merrivale title. Death in Five Boxes has been slowly bubbling its way up my dwindling Carr reading list and I’ve been looking forward to it the whole time. I had big expectations for this book. Carr was pretty much peaking in 1938 – delivering The Ten Teacups (1937), The Judas Window (1938), The Crooked Hinge (1938), The Problem of the Green Capsule (1939), The Problem of the Wire Cage (1939), and The Reader is Warned (1938) all in the surrounding years. If you were to ask anyone to make a Top Ten JDC list, at the very minimum three of those titles would make a showing. If you were to list all of them, I wouldn’t be one to argue.

Death in Five Boxes is a sprint right out of the gate Forensic doctor John Sanders leaves his office late one night and immediately gets pulled into a murder on his way home. The crime scene is utterly bizarre. A bloody sword cane lays on a staircase and upstairs are three incapacitated individuals and one dead body. The three survivors have been poisoned, but will live. What’s really mysterious is the evidence found on them. One victim’s pockets house four watches. Another has the mechanism of an alarm clock. On the third are two different bottles of poison – different than what the party was drugged with.

Shades of The Four False Weapons? I think so. Similar to Carr’s final Bencolin novel, published a year earlier in 1937, the investigators in Death in Five Boxes are thrust into a spiraling nightmare of a crime scene. Simply nothing makes sense. Why was this seemingly unrelated group of people together in the first place? What’s up with all of this weird evidence – watches, poison, alarm clock bits? How were the victims poisoned in the first place? I won’t even get into the mysterious five boxes referenced in the book’s title – that aspect unfolds somewhat late in the story.

Carr fashions the question of how the party was poisoned into somewhat of an impossible crime, although I won’t fully count it. Over multiple chapters, the reader is provided mounting evidence that none of the participants at the crime scene could have had an opportunity to poison the others. In a sense, this is an impossible poisoning – we know that the poison was administered via cocktails, but the testimony of the witnesses suggests that there is no way that could have happened.

Murk things up a bit by the fact that there is one apparent witness at the crime scene – an elderly gentleman who was in the building at the time. The man makes the astonishing claim that everyone involved has gotten away with murder in the past. Before the police can question him further, he vanishes under seemingly impossible circumstances. That impossible aspect doesn’t quite pan out, but the witness’s testimony provides a striking similarity to Agatha Christie’s Cards on the Table – published two years earlier in 1936. Similar to Christie’s novel, the plot of Death in Five Boxes shifts to follow the investigators attempting to unravel the background of the three survivors and examining why they may have been accused of murder.

Carr provides another interesting parallel to Cards on the Table. Just as Christie’s book follows four detectives digging into the past of suspected murderers, Carr expands the detecting beyond the normal confines of his staple Carter Dickson infallible detective – Henry Merrivale. Sure, H.M. seems to have most of this solved from the get go, but the narrative splits between John Sanders, sergeant Pollard (the main character in 1937’s The Ten Teacups), and Chief Inspector Masters. Although the various side characters typically play the role of chasing bad leads and postulating dead end theories, in this book Carr allows them multiple moments of core discovery. Several of these key moments happen in parallel, making for an engrossing read where each chapter toggles between a detective glomming onto a story-changing revelation – often unaware of the progress made by his peers.

It was refreshing to see Masters getting a chance to shine for a change. In most of the Merrivale stories he’s always on the wrong track, and in the later era books his relationship with H.M. turns downright sour. I’m more of a fan of when Carr’s detective foils (Hadley/Master) are working with the lead, rather than being crushed under their heel.

Death in Five Boxes feels a bit more like an early Dr Fell story than an early Merrivale. The mystery isn’t so much focused on an air tight impossibility as it is about unravelling a perplexing set of circumstances surrounding a crime, reminding me more of The Mad Hatter Mystery, Death Watch, The Arabian Nights Murder, or To Wake the Dead. Carr keeps things engaging from start to finish, packing the story with moments of discovery and some fairly tense scenes.

Where the story falls short is the ending – kind of. We’re treated to 30 pages worth of solution, with much of the quality of reveals and misdirection that you expect of a Carr book from this era. However, the two key questions – how the group was impossibly poisoned and the identity of the killer – are well below the author’s standards at this point in his career. Perhaps the solution to the impossibility was revolutionary in 1938, but it packed the modern day freshness of a secret passage. The identity of the killer definitely caught me by surprise, but not exactly in a good way. Overall, this was probably Carr’s weakest set of solutions since his second book – The Lost Gallows.

Overall I’d rate Death in Five Boxes as a strong Carr, although I think it just misses the bar of a book that I’d lend to a friend. Understand that I only lend books that I think are going to be a sure fire hit. With this one, the story is excellent throughout, but it doesn’t quite deliver in the end. I’m curious to see how I look back on this one six months from now.

Alas, I only have one of these early Merrivale stories left – The Punch and Judy Murders (1936). I really think that the Merivale stories between The Plague Court Murders (1934) and Nine — and Death Makes Ten (1940) represent what is quite possibly the best run of Carr’s career. I’m personally more of a Dr Fell fan, but these early HM works really pack the excellent puzzles.

Fun trivia

Chapter nine makes a reference to Ken Blake, who was the point of view character in The Plague Court Murders and The Unicorn Murders. Another character from The Unicorn Murders is referenced, but I won’t mention them by name as I believe they may have been a potential suspect in the book.

This was always an enjoyable find because for a long time just about the only paperback edition was Dell mapback #108, and someone always wanted to buy that edition …

And I agree with you, this is not at the top rank of Dickson, especially with reference to the path of the poison, but it does have that extra dollop of craziness that makes it stand out. I’ve remembered the initial circumstances for decades after I first read this book.

LikeLike

I would have loved to have the Dell map back edition. I bought most of my Carr’s a while back before I became more discerning in the editions I picked up. Still, these Berkley editions are pretty nice.

LikeLike

I think I enjoyed this a little bit more than you — the how of the poisoning is annoyingly unfair because it would take virtually nothing to make it fair, and I do agree that the killer comes out of nowhere in a not completely good way. But I think this was so much more about the construction than the plot, not unlike The Ten Teacups; he’s got these plot threads he wants to overlap, and each contains some brilliant ideas, they just don’t quite join when you bother to stand back and look at it. But when I read it I think I was going through a bit of a constructionist phase, and was somewhat swept away with the intricacy of those individual streams.

Excellent comparisons to The Four False Weapons and Cards on the Table, btw. Mix those two in equal proportions and you pretty much exactly have this book.

LikeLike

Carr constructed a wonderful mystery and I think everything did come together quite nicely in the end – with the exception of the how and the who. There was enough misdirection going on to justify a 30 page solution. Better yet, there was a constant rate of discovery throughout the story – untangling the backstory of each suspect, explaining why the objects were found in their pockets, etc. it’s amazing that Carr paced that all throughout the book and still had enough left in the tank for a 30 page explanation at the end.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like JJm I think I liked the book a bit more than you. I agree it’s not top line material from the author but it is a very enjoyable read, a book I recall enjoying spending time with.

LikeLike

I think you said it perfectly – “not top line material from the author but it is a very enjoyable read”. In fact, for much of the story, it is top line material for Carr.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“the true classic early run of the series (1934-1940)”

I think this is the common consensus – it’s also my assessment, though I’d be willing to discount 1934, which to me is a journeyman year – and I wonder whether this doesn’t also coincide with HM becoming more of a funny guy in the later books. In the earlier stories, he’s a curmudgeon and a cuss, but later on he starts having his hobbies (or something similar, like dictating his memoirs), which is more or less unrelated to the plot and only exists to add some levity to the story.

These things are sometimes funny, sometimes not, but generally the quality of the mystery declines with the advent of HM’s extracurricular activities. Luckily, the Fell stories of that period compensate for that – at least for another few years or so.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is funny how the Merrivale stories start to decline while the Dr Fell stories remain consistent. To be fair, She Died a Lady is a strong showing and He Wouldn’t Kill Patience seems to be a fan favorite.

LikeLike

Great point about how the opening situation is closer to an early Dr. Fell book than a typical H.M. I wonder how Carr decided which detective would get a particular plot?

I wonder if you could expand on how the identity of the killer surprised you but “not exactly in a good way”. When I read DiFB, the revelation packed a real wallop, and Chapter 20 had me believing H.M. was right, and this was in fact the only possible murderer. (It may be relevant that I hadn’t yet read most of the “…Murders” books yet.)

It’s probably a good thing for Dr. Fell’s reputation that he wasn’t in any books between 1949 and 1958, which means he missed the years (1950-54) when the really bad H.M. novels appeared (Mocking Widow [1950] is a real step down from the ones immediately preceding it, including A Graveyard to Let [1949]. Of course, the very good Bride of Newgate is also from 1950, so maybe I’m reading too much into the dates!)

LikeLike

I can’t expand on my issue with the identity of the killer without hinting in a way that would be a spoiler. It was definitely a surprise and there was a nice touch to it when all was explained, but…you might be able to guess at a complaint people would have. It’s funny, because there’s an early Carr book that does a somewhat similar thing with the identity of the killer and in that case I think it is brilliant.

It’s odd that Carr was writing these excellent historicals and The Nine Wrong Answers in the same years as his Merrivale books were deteriorating. The later era Fell books never recaptured the brilliance of the original run, but they never reached the depths of Night at the Mocking Widow or The Cavalier’s Cup.

LikeLike

I think it’s a combination of the following:

Most importantly, Carr was very ill from 1952 to 1954, when the two worst Merrivale novels were published (and no Carr novels at all). We also know that this affected the collaborative “Exploits of Sherlock Holmes” so only six of the stories can actually be called collaborations.

I feel also that Carr started to grow a bit tired with Merrivale (and Fell) and threw himself wholeheartedly into his historical mysteries, which explains why the two Carr books from 1950-51 are very good, while his Dickson novels from 48-50 are a bit poorer than usual. This also fits with 1949’s “Below Suspicion” which divides opinion quite a lot – personally I feel it’s quite weak and incredibly hampered by that hopeless Patrick Butler character. Come to think of it, Butler would have fit perfectly in one of his historicals instead.

It’s also telling that while his non-series novel from around this period, “The Nine Wrong Answers”, is generally lauded, it is also rather too long-winded, something Carr himself later admitted. If he hadn’t fallen ill around that time, it’s certainly plausible that he’d have edited it a bit more judiciously.

LikeLike

I suspect that I read the abridged version of The Nine Wrong Answers. If I recall, it’s rather difficult to track down one of the unabridged editions.

LikeLike

Thanks for the review, which was helpful not just for an evaluation of ‘Death in Five Boxes’, but also for an evaluation of the wider Merrivale canon. I like to save the best for the last, and so I’d better reserve ‘Seeing is Believing’ after ‘Late Wives’ and ‘Bronze Lamp’. I still have that some Merrivale novels left, but I seem to have expended his very best titles, apart from ‘Reader is Warned’.

LikeLike

Understand that there are a lot of divided opinions about those three titles you listed. Popular opinion would probably place The Curse of the Bronze Lamp as the best. Puzzle Doctor lists My Late Wives in his top 10 Carrs. Quite a few people have a sour opinion of Seeing is Believing.

Still, my opinion stands. Seeing is Believing is a classic Carr mystery, right up until it kind of falls flat on its face at the end. Still, a mystery doesn’t have to be perfect to enjoy it. I guess you could draw a parallel to Death in Five Boxes – they are both engrossing reads throughout and then suffer a bit when it comes to the solution (Death in Five Boxes wins overall though). Plus, Seeing is Believing is the only Merrivale after Carr introduced the slapstick humor that is actually funny.

LikeLike

One more thing I need to get off my chest…

WARNING: THIS IS GOING TO BE A SPOILER FOR HOW THE IMPOSSIBLE CRIME IS PULLED OFF IN DEATH IN FIVE BOXES! DON’T READ ANY FARTHER INTO THIS COMMENT IF YOU DON’T WANT TO KNOW!

Okay? Last chance if you’re still reading. All right then… The covers to those Berkley Medallion editions are gorgeous, but the one to DiFB is pretty spoiler-ific! What was the artist thinking?

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was an interesting read after I finished The Arabian Nights Murder. It just didn’t grab me in the way that one did, despite everything. It’s got some interesting characters in, but I found the investigation rather confused, and I kept waiting for things to really get good and they never did. The impossible poisoning method is alright but the who is pretty ropey.

My copy of the book is a UK reprint with a hilariously bad cover – one of those house covers they must have slapped onto all their books, featuring all of

1) a guy with sunglasses wielding a gun

2) the head of a presumably alluring woman

3) a spooky castle with some dead kids on the ground(?)

I guess they really wanted to cover all their bases.

Oh, and the blurb manages to miscount how many people were sat at the table.

LikeLike

I have an edition of The Skeleton in the Clock that comes from the same line as your UK reprint. It has the same guy with the beard (despite no characters with beards), the head of a presumably alluring woman, and some random picture of a guy dead in front of two paintings (I don’t recall any such scene in the book). They seem to have released quite a few of the Merrivale books with this sort of cover, and it just blows my mind, as it isn’t exactly a grabbing theme.

LikeLike