With over 70 books under his belt, John Dickson Carr has a career as a GAD novelist that surpasses most of his peers. Across the span of 42 years are littered a respectable number of classics, a handful of lowlights, and a whole slew of books you really should read if you enjoyed the classics. Categorizing his work may seem simple on the surface – we have the first few books staring French detective Henri Bencolin (published under his own name), the Dr Gideon Fell novels (published under his own name), the Sir Henry Merrivale works (published as Carter Dickson), a handful of non-series works in a similar vein to the Fell/Merrivale stories, and a set of historical novels published between 1950 and the end of his career in 1972.

Or would you divide the work by quality? Surely across the 70+ books there are highs and lows and various shades of in-betweens. What are the better years in Carr’s portfolio? Is there truly a drop off in quality towards the end?

Having read a decent chunk of Carr’s library, I’m starting to feel a vibe for where the better years lay and I have a sense of how his series/non-series works were distributed across his career. In part, this is helped by lists. Whether the categories laid out on Wikipedia or my own chronological list of reviews, I have some sense of Carr’s career arc to the point where I could easily tell you which detectives are in which book and roughly name the publishing year of any of his work.

At this point, it’s tempting to make casual declarations like “Carr’s peak years were 1934-1939” or “the Merrivale works declined before the Fell works.” Is any of this really true though? If we were to lay out the actual timelines for Carr’s library, what would we find?

Well, let’s take a look with the chart below. Although Carr published 70+ novels over his career, there was definitely a burst of activity that tapered off over time. His output started to quickly ramp up as his career began, reached peak output in 1938 with five novels and then took a steep drop down towards 1943 – a year in which he published only one book (She Died a Lady) for the first time since his debut in 1930.

Ok, before we go any further, I’ll call out a few omissions in my calculations before some perceptive soul has a heart attack. In all of the charts that I’ll use, I purposely exclude:

- The Murder of Sir Edmund Godfrey (1936) – this is historical non-fiction and somehow feels out of place.

- Devil Kinsmere (1934) – Carr’s first attempt at a historical work published under the name of Roger Fairbairn. This was later published as Most Secret (1964), so it seemed odd to count it twice – although I’ve heard both versions are fairly different.

- I didn’t count any of the short story collections, because, well, they’re short stories and that doesn’t really count. I also haven’t counted the novella The Third Bullet.

Ok, so where were we? From 1943, Carr maintains a slower pace, vacillating between one and two novels a year. 1954 finds us with the first year without a single novel published. From this point on, we maintain a steady diet of one novel a year with the exception of a few dry years and 1968 – the last year Carr ever published two novels (Dark of the Moon and Papa La Bas).

So what can we take away from all of this? Well, 1933 through 1941 were clearly years of inspiration for Carr. For one reason or another, his output slowed after that point. I haven’t yet read a Carr biography, so perhaps someone else is aware of what circumstances could have led to the leveling off. Perhaps the author was financially well enough off that he could let his foot off the gas a little and enjoy life.

Now, let’s break the data down a different way to see what it might show. Below I’ve categorized the timeline by series detective, creating additional categories for non-series contemporary works and historicals.

The Bencolin books are no surprise – four titles in a row at the beginning of Carr’s career, plus a blip later on for the detective’s final novel – The Four False Weapons. Fell vs Merrivale may be a bit more interesting. There are slightly more Fell books from 1933 through 1941, although this is mostly swayed by the detective getting a one year head start on Merrivale. Lop off 1933 and things become a bit more even. Between 1942 and the final Merrivale novel in 1953 (The Cavalier’s Cup), Fell seems to fall out of favor, appearing in less than half of the work between the two detectives. Of course, Fell won out, with a run of five books between 1958 (The Dead Man’s Knock) and his swan song – Dark of the Moon (1968).

As for the non-series works, well, there weren’t that many of them. Immediately following the initial run of Bencolin books, Carr played around with alternative detectives in Poison in Jest (1932) and The Bowstring Murders (1933). Outside of that, he only released five additional non-series works. Most of these seemed like intentional standalone titles. The exception is The Emperor’s Snuff Box (1942), where you could imagine Dr Dermot Kinross gracing the pages of another work. Alas, it wasn’t meant to be.

When I think of Carr’s historical works, my mind tends to divide them into two categories – the “classics”, a span starting with The Bride of Newgate (1950) and running through Most Secret (1964), and the “downward slide”, the final run of four novels that perhaps aren’t held to the same high standard. Of course, this is my brain creating it’s own weird categories with no real basis in fact since I haven’t read them all yet.

The timeline is kind of interesting to me in that effect. The first two historicals (The Bride of Newgate and The Devil in Velvet – 1950/51) are actually separated from the rest of “the classics” by a few years. In fact, that separation is just as wide as the gap between Most Secret (1964) and Papa La-Bas (1968). If anything, it’s the run of Captain Cut-throat (1955) through Most Secret (1964) that’s held together most cohesively by time.

Another way to break down Carr’s library is by quality. Which years are really the best? Which years are the weakest? Was there a period of time where Carr was truly at his peak?

Well, naturally, I have opinions on this regardless of looking at the data. My gut feel is that Carr was in his prime from Hag’s Nook in 1933 through 1939, the year in which he published The Problem of the Green Capsule, The Problem of the Wire Cage, The Reader is Warned, and Fatal Descent. You’ll notice that those years overlap considerably with the large hump in the author’s output. Of course, he released some of his best work after that period (The Emperor’s Snuff Box [1942], The Case of the Constant Suicides [1941], Till Death Do Us Part [1944], She Died a Lady [1943], and He Who Whispers [1946] being obvious examples). But, those stories were released in leaner years, either in which they were the only book published, or accompanied by a weaker title.

When was Carr at his worst? Well, conventional wisdom would say that he took a downward turn towards the end of his career as most long-lived authors do. My gut instinct is that this took place around 1965 (The House at Satan’s Elbow), but I haven’t read enough later year books to really comment. In fact, the later year books that I’ve read haven’t been that bad. The one Carr novel that I haven’t enjoyed so far is Night At the Mocking Widow (1950) and that was followed by such titles as The Devil in Velvet (1951), The Nine Wrong Answers (1952), and Fire, Burn (1957), which I think many fans would agree are among his best.

Well, enough of my opinions, let’s look at the actual data. Err, well, this is actually going to lean heavily on opinion. How else can I quantify the strength of his work? So, whose opinion am I going to base this on? The result of some legendary fan poll? Nope, mine, and mine alone.

Now, I’m not going to actually tell you the rating that I’ve given each book (that will come in later posts), but I will reveal my ranking scores:

5. An absolute must read classic. Example – The Problem of the Green Capsule

4. A book that I would willingly recommend to someone just getting started with Carr (in fact, I’ve actually lent out every book that has this score.) Example: The Four False Weapons

3. A book that I found extremely enjoyable, but isn’t quite a book that I would hand to someone as one of their first 10 reads. Example: To Wake the Dead

2. A book that has considerable weaknesses but also possesses redeeming qualities. Example: Dark of the Moon

1. A book that I really didn’t like. Example: Night at the Mocking Widow

Having assigned each book that I’ve read one of these values, I crunched the numbers and came up with this spread:

Well, hold off, you can’t really interpret the data yet. Keep in mind that I still have 24 Carr novels to read. As such, some years have a much lower score than they’ll eventually be awarded. The most obvious victim in 1936, the year Carr published The Arabian Nights Murder and The Punch and Judy Murders. Based on reviews I’ve read, I’m guessing these will get either a three or four score when I finally get to them.

As things stand, the obvious outstanding years are 1938 (The Four False Weapons, To Wake the Dead, The Crooked Hinge, The Judas Window, and Death in Five Boxes) and 1939 (The Problem of the Green Capsule, The Problem of the Wire Cage, The Reader is Warned, and Fatal Descent). Of course, those are each years in which Carr published over four books. Naturally they’re going to be ranked high.

Likewise, the later years are ranked low, which matches the conventional wisdom that Carr’s career tapered off. But, he was only publishing a book or two per year, so of course those scores are going to be low.

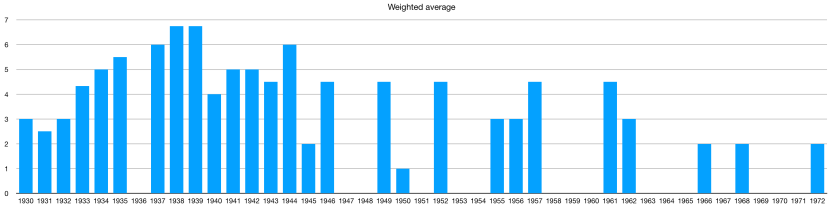

Let’s even the field by taking the average score. This is going to ignore the number of books published (to an extent) and instead purely look at the average quality of the books for each year.

Well, that looks a bit better. The data somewhat aligns with my theory that Carr’s better years started in 1933 (well, it actually suggests 1934) and stretched to…..wait a minute!!! We have Carr maintaining a peak well through the early 1940s and actually peaking in 1944 (Till Death Do Us Part, He Wouldn’t Kill Patience [unread]). Furthermore, he holds strong to an extent through 1961 (The Witch of the Low Tide). How can that be?

It turns out that using an average has its own issues. 1944 is called out in my chart as Carr’s peak because the only book that he published that year that I’ve read (Till Death Do Us Part) received a five. 1938 and 1939, which were previously heralded as the magic years, are being dragged down by a few three and four scores, even though they’re also heavy on fives as well.

This leads to an interesting question – what constitutes a strong year? If an author pumps out four books that get a four/five rating in one year, shouldn’t that be better than a year in which an author only releases a single book receiving a five rating? Quantity, especially when it consists of high quality, must be a factor!

Ok, so I thought about this one for a while. I thought about it so much that I’m embarrassed to say that I actually took several statistics classes in college. Well, that was a long time ago and I have to say that I’m still grasping for the right way to do this.

So, I devised a bit of a hair-brained scheme that would put any of my statistics teachers in the grave. Oh well, I’m going for it.

I’m going to take the average and modify it. If a book received a four, it will receive a plus .5 bonus. A five will receive a plus 1 bonus. Let me illustrate:

Year 1 – four, four, five, five = average of 4.5 + bonus of 3 = 7.5

Year 2 – five = average of 5 + bonus of 1 = 6

Under this scoring system Year 1 is seen as a stronger year because of the feat of pulling off four titles that all scored a four or better. That ultimately wins out over Year 2, in which only a single book was published, albeit with a five score.

Before I lose people with the dryness of the math, let me pose the question outright – what to you would constitute a top year in a writer’s career, assuming multiple books published in some years? Maybe that seems to be a nonsensical question, but let me offer a concrete inquiry which may hold some weight. If a long lost John Dickson Carr book was discovered, what year would you hope it was written? My gut reaction is 1938 or 1939, as Carr’s plotting was really in full swing. This would be a book with shared brethren of The Four False Weapons, The Crooked Hinge, The Problem of the Green Capsule, The Problem of the Wire Cage, The Judas Window… Does the evidence support it though?

It appears so. The adjusted average looks a lot more in line with my feelings for Carr’s catalogue than the raw average. 1938 and 1939 have risen to the top. 1944 still scores well, but it’s been brought down by the fact that it doesn’t have the sheer quantity of quality output.

1935 through 1939 appears to be the peak run, with 1944 being a brief return to form. Overall, the time period between 1933 and 1946 scores well, the one exception being 1945 (brought down by The Curse of the Bronze Lamp, which for me was just ok).

There is still evidence that the later years were weaker, although you’ll notice that the decline doesn’t really happen until 1966 (Panic in Box C). Of course, I still have quite a few later year books to read, so we’ll see how this plays out.

As I mentioned earlier, the scoring is all subjective to my tastes, but more importantly, it’s influenced by what I have and haven’t read so far. Here’s a chart showing the count of books I’ve read (in blue), and the books that I still have to read (in red).

1934 and 1936 are earlier years where I still have two books each to read. I suspect their scores will probably change significantly, as I tend to like Carr’s stories from that time period the most. 1944 is another year that may get an additional boost, as I’ve yet to read the highly regarded He Wouldn’t Kill Patience.

Then there’s the run from 1947 (The Sleeping Sphinx) through 1971 (Deadly Hall). About two thirds of the books I have left to read come from this period. I’m guessing those stories will primarily alternate between scores of two and three, but that’s just a guess at this point.

Being able to visualize my remaining reads also helps influence how I might approach them. I enjoy the earlier works the most, so I don’t want to rush through them and be left only with the tail end of the chart. My hope is that as the red markers turn blue, I still maintain somewhat of an even distribution of red throughout the entire timeline.

Yeehaa! Maths is fun, just like logic. 😉

You know what you could have done? Just skip the years entirely. Just make a long row of all novels published, assign them your grade value and see how that curve looks.

Or if you really want to do it by year, then just add an extra 0.5 for each book in a prolific year. That gives the “dogs” of prolific years a compensation for having had so much competition.

Then you don’t have to factor in +0.5 for grade 4 and +1 for grade 5, because to be honest, what you did now is just add extra points to a book because it’s good. If you’re going to be that arbitrary, then why not give 0 points to the lowest category, 2 to the next lowest, 5 to the middle one, 10 to the second highest and 100 to the highest? It’ll skew the results even more towards years with good books. 😉

As for your conclusions, I agree with them overall. I’d say that 1935 is Carr’s first year of greatness and it continues till sometime in the early 40s.

LikeLike

Eliminating the years entirely would definitely make for an interesting chart. The years are somewhat arbitrary markers anyway – I can imagine some books were written in one year but published in the next. Eliminating the years would give a good view of the pure quality of the books and it would be interesting to see where the peaks and dips lay in the more prolific years.

The early forties gives us books like The Man Who Could Not Shudder, And So to Murder (haven’t read), Seeing is Believing, and The Gilded Man. I personally really like the three of those that I read, but I can also appreciate that they are a drop in quality from the proceeding years (and I scored them all as a three). As such, I have to claim 1939 as the end of the true peak.

Of course, with that said, some of Carr’s absolute best work comes out of the early 1940s – The Case of the Constant Suicides, Till Death Do Us Part, Nine — and Death Makes Ten, He Who Whispers, She Died a Lady (I personally find this last one to be a bit over-rated, but I’ll accept the wisdom of the masses). It’s interesting how he started to waver between such highs and (relative) lows.

LikeLike

As you yourself note in a later comment here, the Fell stories from the early 40s are still of the very highest quality:

“The Man Who Could Not Shudder”, “The Case of the Constant Suicides”, “Death Turns the Tables” and “Till Death Do Us Part”. (And I’d also add both novels from the late 40s, “He Who Whispers” and “The Sleeping Sphinx” to this batch.) It’s not really until “Below Suspicion” that the problems start to seep in.

Meanwhile Merrivale tapers off a bit:

“And So To Murder” is so-so (and cheats)

“Nine – And Death Makes Ten” is great

“Seeing is Believing” has problems (e.g. a huge cheat), but is overall okay

“The Gilded Man” is again mainly okay

“She Died A Lady” has a great killer but a disappointing impossibility

“He Wouldn’t Kill Patience” is a great mystery with a disappointing killer

“The Curse of the Bronze Lamp” has yet another great impossibility, but seems a bit convoluted otherwise. Another disappointing killer.

As has been said otherwhere, there is a slippery slope in the Merrivales where the focus on our beloved H. M.’s hi-jinks and slapstick increases.

LikeLike

I’m actually a big fan of Below Suspicion. The mysteries are spot on, the solutions are great, and Patrick Butler is supposed to be unlikeable. My one issue with the book (covered more in depth in my review) is the way that the killer announces their role in the affair, which was simply cheesy.

Your summary of She Died a Lady captures it perfectly. The puzzle is so good, but the solution is a bit of a let down. Great killer though.

LikeLike

This is great, dude, I’ve been waiting to have enough time today to sit down and tell you how impressed I am with your approach to analysing Carr’s career in this way. His peak extended well into the 1940s…sure, it’s all subjective, but I maintain there’s some stuff there which — when you bear its intent in mind — is easily as good as his mid-30s stuff that was pure puzzle and plot and scheme. but then, to be fair, I’m still yet to read a Carr novel I actively dislike or can say nothing breathless about (even The Bride of Newgate — goddamn, those opening five chapters are amazing).

We shall, I’m sure, have many opportunities to refer back to and amend this over the years; excellent work.

LikeLike

Yeah – there is definitely going to be a sequel to this post. Once I’ve completed Carr I’ll be posting the actual ratings and then run back through the ultimate results. Plus, I already have some other thoughts for how to visualize the data, so maybe there will be an intermediate post.

I’d be curious to see this type of analysis done on other prolific authors such as Christie or Queen (hint, hint Brad). Even a chart showing how many books were published each year would be interesting. Throw in a breakdown of Christie’s series detectives or Queen’s phases…

As I commented to Christian up above, Carr definitely published some of his best work in the 1940s. And of course, that’s to say nothing of the historical output from the 1950s! You may gasp, but I’ve rated all of the historicals as a three. By my own definition, I would not lend any of them to a Carr novice, and so they don’t qualify as a four. With that said….man, you know how much I love those historicals!

LikeLike

Interesting synchronicity – I’m working on my own “rate Carr books” post that takes a different approach.

One reason Carr published fewer novels during the 40s and early 50s is that he was putting a lot of his time into writing radio plays instead. Here’s a blog post with a lot of information on them: https://bloodymurder.wordpress.com/john-dickson-carr/radio-plays-by-john-dickson-carr/

I see you made a comment there!

If I had to pick a year for my undiscovered Carr novel, I think I’d pick one from 1940-1945, just because World War Two is a subject I enjoy, and he was very good at incorporating it into many of his plots (And So to Murder, Nine – and Death Makes Ten, She Died a Lady, He Wouldn’t Kill Patience, The Case of the Constant Suicides – hmm, it’s interesting that most of the wartime colour is in books by “Carter Dickson”, while Carr’s books of the period under his own name are usually set before the war.)

LikeLike

Ah, yes, the role of the radio plays dawned on me at one point while writing this and then I lost track of the thought. It makes you wonder what additional novels we may have missed out on if not for the plays…

On the topic of “the lost Carr book” – it struck me that I might answer differently if I were to pick a Fell or Merrivale novel. I haven’t looked at the data yet to verify this, but my gut tells me that I like earlier Merrivale titles (1934-38), while I like my Fell a bit better later (1935-1946). Of course, I have a few titles that I have yet to read that could alter that theory.

I’m looking forward to seeing your post on rating Carr!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It should also be noted that Carr wrote several of his short stories between 1935 and 1940 – I think most of them are actually from 1938-1940, so even a shorter timespan – which says something both about Carr’s workload during those years and about the expected quality of these stories.

LikeLike

This is utterly brilliant. I will refer to this often. Excellent work sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great fun – on the whole I like his stuff all the way through, from his short stories in the 1920s well into the novels of the 1960s (most agree on WITCH OF THE LOW-TIDE for instance).

You definitely have to read Doug Greene’s superb biography of Carr, THE MAN WHO EXPLAINED MIRACLES. Throughout the 1940s Carr was an enormously prolific authors of radio plays, so that took a lot of his time. And most of those were utterly superb by the way. Also, there were paper shortages during the war, so he couldn’t keep writing at the same pace even if he had wanted to. The damnit, the short story collection should count!

Incidentally, you can find a list of his mystery radio plays (he wrote lots of other kinds too, predominantly war propaganda) at my old blog: https://bloodymurder.wordpress.com/john-dickson-carr/radio-plays-by-john-dickson-carr/

LikeLiked by 1 person

As with you I really do like Carr’s stuff all the way through, including the curiously maligned The Hungry Goblin. You’re right to single out the excellent The Witch of the Low Tide, which in my current rankings is his last “great book”. I still have five books that followed it left to read, so we’ll see if that title holds.

I have The Door to Doom and Other Detections, which includes a handful of Carr’s radio plays. There’s another collection that I know I’ll have to track down – The Dead Sleep Lightly. I’ve listened to a few of the radio plays and have to say that I prefer the written form to the spoken, but that’s just me.

The short stories collections are problematic because I don’t know which year to include them under. Is it the year that the collection was published, or the year of the individual short stories? Plus, the big factor is that I’m holding off on the short stories until the very end, as I know that Carr recycled a few tricks and I’d rather have a short story ruined than a full length novel. Don’t worry, I’ve read a handful of the shorts, most importantly The House in Goblin Wood.

LikeLike

As I mentioned above, the short stories were mainly written during the late 30s (though there’s obviously a lot of juvenilia from his school papers before he became a full-time author, some of it featuring Bencolin, as well as some stories from the 50s). The Greene biography Sergio mentions above has all this information, though if you want it before you get to reading it I could send it to you, since I have it collected in my own Carr collections. (Shameless plug: Reviews of which will appear on my blog some time next week, if everything goes as planned.)

LikeLike

I’ve been waiting to see if you would get to Carr – I think your first post had suggested you wouldn’t be covering him.

If I can ever figure out how to get comments to actually work on blogspot while using a wordpress account, I’ll pitch into the discussion.

LikeLike

I know what you mean about spoilers – my feeling is that we should give the dates of when a volume is published – after all, novels are not dated by when a manuscript was completed or, as was so often the case then, a part of the novel was serialised ahead of the book version. DEPARTMENT OF QUEER COMPLAINTS is a classic and deserves to be properly mentioned no matter what.

LikeLike

Oh no, I’ll get to Carr. I just won’t be using any of the regular collections, because 1. their content is rather arbitrary and 2. I’m a completist and it’s easier just to go through each story once instead of having duplicated stories all over the place.

I just need to get Agatha Christie out of the way first…

LikeLike